Manipur's unrest: A threat beyond its borders

Who would have imagined that drone warfare would come to India’s Manipur?

Yet, it has happened. On September 7, reports emerged of casualties from drone strikes in the region, marking a troubling escalation of violence. So far, 12 people have been reported killed.

This situation echoes the infamous events of May 3 last year, when two women were paraded naked in the streets of Thoubal district, both serving as catalysts for further violence and suffering.

The civil conflict has been ongoing for over a year, resulting in hundreds of deaths and thousands of injuries. The drone strike on September 7 represents a significant turning point in the conflict, potentially heightening tensions and instability throughout Southeast Asia.

After a relative lull in violence in recent months, this sudden surge is grabbing international media attention.

In addition to drone strikes, there have also been rocket attacks. The assaults by Kuki militants appear to be unprecedented. In response, the state administration has implemented an internet blackout and imposed curfews in three districts: Imphal West, Imphal East, and Thoubal.

Chief Minister Biren Singh has ordered targeted killings of the militants. Despite these measures, it seems the Indian government was not fully prepared for the situation.

Questions arise regarding Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s efforts to stabilize the region; he has not visited Manipur since last May, which may indicate escalating security challenges.

Troubled stance of Modi

administration

Modi's BJP party has long supported the Maiteis, the Hindu majority in Manipur, a stance that has alienated ethnic minority groups like the Kuki and Zo.

These minorities have formed an alliance against the Maiteis. Since May 4, 2023, the Kuki-Zo alliance and the Maiteis have engaged in sporadic clashes, with Indian government forces intervening.

However, there are allegations that Indian security personnel have frequently sided with the Hindu Meiteis against the Kuki-Zo communities.

The organization Human Rights Watch (HRW) has accused Indian security forces of conducting partisan killings during the ongoing conflict.

This could explain why the Kukis are now targeting not only the Meiteis but also government forces, resulting in the deaths of six known security personnel so far.

Despite the initiatives implemented under Chief Minister Biren Singh's direction, many people are dissatisfied with how the Indian administration is managing the situation.

This discontent is clearly evident in student demonstrations calling for the withdrawal of security forces from Manipur. The Times of India reported that some protesters even attempted to storm Biren Singh’s residence, underscoring the growing frustration among youth regarding the state’s actions.

Manipur University examinations have been postponed, and thousands of troops have been deployed to restore order—an indication that the situation has become quite “war-like."

It's important to recognize that these eruptions of violence are not isolated incidents. They stem from decades of grievances among the region's ethnic communities in eastern India.

In April of last year, the Manipur High Court recommended granting the Meitei community special tribal status, a move condemned by the All Tribal Students’ Union Manipur.

This recommendation reflects the long-criticized caste system that persists in India, despite the country's status as the "World’s Largest Democracy."

The caste system exemplifies the famous Orwellian phrase, “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.”

Initially, the All Tribal Students’ Union Manipur organized peaceful protests, but violence erupted between the Kukis and Meiteis following one of these demonstrations.

Shortly thereafter, videos surfaced showing two women from the Kuki-Zo community being forced to walk naked, plunging Manipur into further turmoil.

History of tribal problems in Manipur

Manipur was once an independent kingdom before the British Empire invaded South Asia. In fact, Raja Jay Singh, the king at the time, signed a trade agreement with the East India Company in 1762 to protect his territories from Burma (now Myanmar).

The British subsequently sought to relocate new populations to Manipur to bolster defenses against Burmese invasions. In response, King Jay allowed people from the Kuki Chin Hills of Burma to settle in Manipur, shaping the region's demographics, which now include Kukis, Nagas, and Meiteis.

Unfortunately, this initiative did not prevent further attacks from Burma. Between 1819 and 1826, Manipur was occupied by the Burmese Empire until the first Anglo-Burmese War, which ultimately led to British control over what is now Myanmar.

For Manipur, this brought a brief respite, but it was short-lived as the region passed from one occupier to another.

Manipur remained a British protectorate for several years until a palace coup in 1890. The following year, the Anglo-Manipur War broke out, resulting in a crushing defeat for the Manipuri resistance.

In the aftermath, British authorities drew an arbitrary line in the state, ensuring that the Meitei valley remained under colonial control.

In protest, the Kukis launched attacks on British troops stationed in Manipur. When World War I began in 1917, the puppet ruler imposed by the British was instructed to send men from Manipur to the frontlines in Europe.

The Kukis refused to comply, leading to intensified hostilities with the colonial powers. Once again, the Kukis were defeated and forced back into the forests, a significant event that shaped the demographics we see in Manipur today.

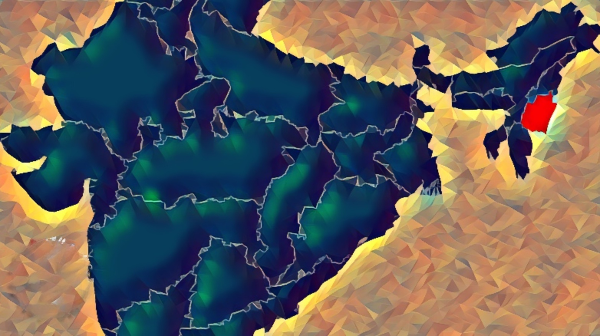

The Kukis, predominantly Christians and making up about 28 percent of the state's population, inhabit the mountainous regions, which cover approximately 90 percent of Manipur’s area.

In contrast, the Meiteis, who account for 53 percent of the population, reside in the valley, which constitutes only about 10 percent of the land.

Despite this, relations between the two communities were generally harmonious for a long time. The battle-hardened Kukis were often relied upon by Manipuri kings, and at times, they served as personal bodyguards. A notable example is Bodachandra Singh, the last king of Manipur, who employed Kukis in this capacity.

When India gained independence from British rule in 1947, it also annexed Manipur, making it part of India. However, this was not the desire of many in the state.

The Naga community initiated an insurgency against Indian rule, demanding their own state. Given Manipur’s history as an independent kingdom, the Meiteis—who were the monarchs—saw this as an opportunity to reclaim their sovereignty from the new Indian authority.

It's not unreasonable to think that many Meiteis began to view the Kuki community as outsiders, since the British had relocated them to Manipur following the trade agreement between Raja Jay Singh and the East India Company.

Meanwhile, the Kukis sought autonomy, referring to it as “Kukiland.” This pursuit of autonomy doesn’t imply a separate nation within India; rather, it highlights their desire for self-governance.

Ultimately, this has led to the emergence of three insurgencies among the communities, which have become increasingly adversarial. The situation has not only persisted but has also worsened over time.

Why has violence escalated in recent

times?

Indian think tanks, such as “The Northeast Affairs,” consider the notion of Kukiland a national security threat. Furthermore, the ongoing civil war in Myanmar has displaced many Kukis from Chin State, their ancestral homeland from which they were relocated to Manipur by the British.

The Kukis are also engaged in a struggle against Myanmar’s military dictatorship, leading to reports of ongoing arms smuggling along the India-Myanmar border.

Currently, the Kukis face threats from both the Tatmadaw (the official name for Myanmar’s armed forces) and Indian defense forces. The border between India and Myanmar is characterized by complex terrain of jungles and mountains, making efficient patrols challenging.

This environment provides Kuki insurgents with opportunities to use hit-and-run tactics against government personnel in both countries and offers them effective hiding places from surveillance aircraft.

Consequently, it is likely that both India and the Myanmar junta will face significant challenges in their efforts to suppress these insurgencies.

The lack of effective control by both governments over the Chin borders highlights the challenges posed by these armed groups. However, the Tatmadaw and Indian agencies have cooperated well in the past.

For instance, the Hindustan Times reported in 2020 that the Tatmadaw handed over 20 militant leaders active in Assam and other northeastern states to the Indian government, facilitated by negotiations led by National Security Adviser Ajit Doval.

In recent years, militants have also been seeking refuge in Bangladesh.

One notable armed group is the Kuki Chin National Front (KCNF), founded in 2008 by Nathan Bawm from the Bawm community in the Chittagong Hill Tracts.

Like the Kukis of Manipur, the Bawms are predominantly Christian and share ethnic and military ties with Kuki militants in Chin and Manipur. The Bengali outlet Protidiner Songbad reported that KCNF fighters received training in Manipur and Chin.

How is Bangladesh affected?

A particularly notable incident was the March 12, 2023 ambush on a Bangladeshi military patrol in Bandarban’s Rawangchari, which resulted in the death of an officer.

More recently, on April 2, the KCNF launched a significant attack on a Sonali Bank branch in Ruma Upazila, stealing nearly 15 million taka.

The bank manager was also kidnapped and later ransomed to security forces for an additional 1.5 million taka, along with the seizure of various weapons.

This operation showcased the KCNF’s ability to execute surprise attacks effectively. The group is reportedly working towards establishing an independent state for the Bawm people, covering nine sub-districts in Rangamati and Bandarban.

In terms of regional security in Southeast Asia, particularly for Myanmar, Bangladesh, and India, the Kukis have built a formidable reputation that poses a potential threat.

It’s crucial to recognize their demands as legitimate. Discrimination against ethnic minorities often leads to long-term instability, as the current border situations in these countries demonstrate.

State actors must understand that granting autonomy does not equate to ceding territory. It is urgent to address the rights of these communities before the situation escalates beyond control, making it too late for reconciliation.

—-

Chowdhury Taoheed Al Rabbi is a freelance writer